Scotty: Prepare to Scale Up!

Blog Posts

A first-time COO of a start-up recently asked me what he can do to prepare for scaling up their company? I asked him to elaborate with some examples of specific challenges and impediments.

He was trying to figure out how to prepare for balancing resources and commitments and that he was stumped by a Catch-22: In the future the company would need to balance customer service with new product development. However how they currently handle these roles is not how they would handle them in the future. So merely scaling the current approach would not be relevant. And even the idea of envisioning how they would handle this balance in the future requires that they know something about it–which they don’t–means that any assumptions are baseless conjecture. Therefore basing plans on these assumptions could be foolhardy as they won’t have confidence in any modeling of the future state from which to run projections.

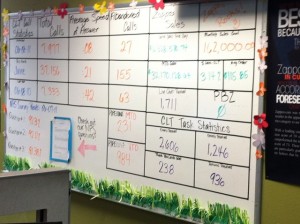

Customer service metrics at Zappos where metrics are used to balance workload not enforce response speed.

This is further confounded by the fact that they’re currently too small to even have a balancing problem yet!

This is the type of question that typically only occurs to people baring the scars of prior experience to recognize it. That this young COO was already asking it is a good omen (for their company). In fairness, the company also has a seasoned CEO and a cadre of competent advisors. Not to diminish his big-picture forward-thinking, his other questions made it clear that scars or no, this guy was cut from the cloth of operations people.

When the seemingly obvious data isn’t available we merely have to widen our view. We need to see the overall effect of the situation’s dynamic and find the data that helps us to understand that.

In this case, the data turns out to be fairly simple (and abundant). Their current situation–very common, by the way–is that the COO is playing the role of customer service handler. This technically competent COO can handle many of the customer service inquiries. He rarely needs to “escalate” issues to development-types when the matter is truly in the weeds of the product.

Despite the rare need to escalate he could already see that this was not a scalable approach. He also saw that they were a long way from growing a distinct customer service capability and even further from growing a tech support group distinct from the product development group.

For the time being the most likely approach would be to continue to use product developers to field only select field issues. The most likely next evolution in the company would see growth among product developers and testers long before it saw growth in specialized skills or capacity to handle customer service calls. Therefore the most likely customer service solution for the next while would rely on figuring out how to allocate developer time. How much time would go towards handling customer matters and how much time to continuing their work on new product development. In other words when planning the company’s ability to deliver new features and products, instead of assuming developer time is always used for new stuff, some percentage of developer time would be reserved for customer services.

To do this he would need to better understand how much time product people spend (lose) on dealing with customer service issues escalated to them. Immediately a challenge appears: How does he collect the developer time consumed by customer service issues without disrupting them?

He could survey them over lunch. He could try to sit around capturing data–old school. But I advised him that none of these are necessary. The answers didn’t lie in how much time the developers were spending on customer service issues. The answers are in how many service issues they get.

All it takes is to take advantage of data already at hand and easily available. The data the COO can observe for himself. Since he handles the issues himself and decides what gets escalated he had access to all the data he needs.

The gist of the necessary data is straight-forward: Customer service needs arise from their fielded products. Therefore, you know how many systems|units are deployed. From these you can measure:

- # customer issues

- which customers have issues

- the types of issues customers have

- how long it takes you to deal with the calls

- # of issues you need to escalate

- types of issues you need to escalate

- how long before you hear back from the development people

- whether or not you needed to rattle cages to get an answer (THEN how long before you got an answer after rattling cages)

- contrast requests for new features to issues with existing features

These are just the beginning. Basically, aside from calls requesting new features, most customer inquiries are due to some shade of quality somewhere in your workflow. The best way to scale customer service is to start by minimizing quality issues that escape into your customers’ hands.

The end-state, eventually, is a product development process instrumented to identify the load balancing necessary as a function of quality, not only volume of fielded product. Surely as more product is fielded they will need to scale the ability to respond to customers, however, if fielded product is the only metric it will never be right. The need is to be predictable and the lack of predictability is due to variation in quality (whatever way one chooses to define that). Scaling without understanding this variation will be an inefficient and expensive crap shoot.

-

2018-Jul-12

Old Dogs, Not-so-new Tricks: A Catch-22 for Private Equity Portfolio Companies - View The Blog

-

2015-Feb-17

Start-Ups Fail. But Not Why You Think. - View The Blog

-

2015-Feb-09

Don’t Do This! 5 Mistakes Your Start-Up is Probably Making - View The Blog

-

2015-Jan-30

Scotty: Prepare to Scale Up! - View The Blog

-

2015-Jan-12

Do Software Companies Need a COO? - View The Blog

-

Entinex

A management consulting firm focused on business' performance. The recognized world expert in bringing lean principles into harmony with heavy regulations and governance. Learn More -

Agile CMMI® Blog

The blog that started a revolution. Directly from the world's recognized authority on Agile & CMMI. Learn More